above suspicion

I have found myself of late coming under some (albeit generally light-hearted and well-meaning) criticism directed toward the challenging linguistic gymnastics that I appear to enjoy imposing upon those who might read what I have put to pen. To those who would so dare to unsheathe their sharp tongue to lash out at my, admittedly at times, pedantic prose I will simply state that for you the pain will assuredly increase if you care to continue to read what I have so carefully constructed. There will be no apologies, no public self-flagellation or admission of addiction or sinfulness, and most emphatically, there will be no attempt to restyle what I write to the level of a guttersnipe.

The Image We Convey

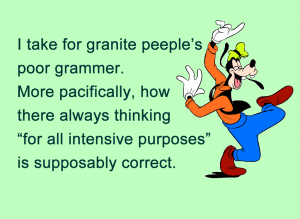

Among those for whom the world holds in the highest regard you will fail to find so much as one so elevated who is unwilling or incapable of producing a cogent, well-phrased, intelligent thought. As B.R. Myers so aptly states, “People who cannot distinguish between good and bad language, or who regard the distinction as unimportant, are unlikely to think carefully about anything else” and I might add that they will find themselves wedged tightly between the ranks of the unimportant and forgotten. Those who fail to educate themselves in the appropriate and proper use of language show but low regard for their own character and reputation. It is as if it was their expressed desire to make themselves look foolish or uneducated or, perhaps worst of all, ignorant.

A poorly written sentence grates like fingernails scratching upon a chalkboard, sending chills down the spine and rattling the nerves. An encounter with a tortured phrase forces the mind to slam on the brakes to avoid collision with the mangled mayhem that strains the eyes. Coarse, crude language reduces to rubbish any statement in which it is injected, provoking illegitimacy to any argument and disparaging the person who would enjoy living in the gutter. And misspelled or misused words only serve to raise confusion and doubt concerning the probity of what has been written and the veracity of the abuser.

Edgar Allan Poe wrote that “A man’s grammar, like Caesar’s wife, must not only be pure, but above suspicion of impurity.” While I will forgive Poe for placing the onus of good grammar solely upon the male half of the species, I wholeheartedly agree with the intent of his sentiment. Ben Marcus wrote that “a misspelled word is probably an alias for some desperate call for aid, which is bound to fail.” I might also add that the misuse of any number of homophones is a sign of a mind in the final stages of terminal mental atrophy, for there is no excuse for the improper use of “its” or “it’s”, “your” or “you’re”, “there” or “they’re” or “their”. And for those who might struggle with the meaning of “homophone” allow me to say that a homophone is a word that is pronounced the same as another word but differs in meaning, and may differ in spelling.

A well-written line, one that gives homage to the language, provides clarity of thought and promotes reasoned understanding of ideas. A poorly constructed sentence, one filled with grammatical errors, misspellings, and poorly chosen words only serve to obfuscate and confuse, to which Michel de Montaigne states, “The greater part of the world’s troubles are due to questions of grammar” and Constance Hale wrote that “The flesh of prose gets its shape and strength from the bones of grammar.”

In The Perpetual Calendar of Inspiration, Vera Nazarian wrote that “Each letter of the alphabet is a steadfast loyal soldier in a great army of words, sentences, paragraphs, and stories. One letter falls, and the entire language falters.” It is no small thing when something as horrific as war or genocide should result from the utterance of a single offensive word or phrase. Words matter, not so much to the one who utters or writes them, but to those who hear or read them. It is thus incumbent upon those who would speak or write to do so with great care, accuracy, and clarity of thought.

Just as Margaret Wolfe Hungerford once wrote that “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder” we should always be mindful that words expressed should always bear beauty and truth to the mind of the receiver. Someone once said, “Say what you mean and mean what you say” and that is true, but what is truer still is to insure that “what you mean to say is what I hear you say.”

As for those who complain that I often use multi-syllable unfamiliar words, I freely admit to such practice for I would rather stain with eloquence than smear with blandness. A new unfamiliar word is like a breath of fresh air that refreshes and reenergizes the written page. I can only offer this advice that quite interestingly comes from two worthy writers: My mother and William Safire. Safire said, “When I need to know the meaning of a word, I look it up in a dictionary” while my mother would simply point to the dictionary and say, “Look it up.”

Let me say a few final words on this subject. William Safire once quipped, “Is sloppiness in speech caused by ignorance or apathy? I don’t know and I don’t care.” To which I am want to add, neither do I.

Caesar’s Wife

above suspicion

I have found myself of late coming under some (albeit generally light-hearted and well-meaning) criticism directed toward the challenging linguistic gymnastics that I appear to enjoy imposing upon those who might read what I have put to pen. To those who would so dare to unsheathe their sharp tongue to lash out at my, admittedly at times, pedantic prose I will simply state that for you the pain will assuredly increase if you care to continue to read what I have so carefully constructed. There will be no apologies, no public self-flagellation or admission of addiction or sinfulness, and most emphatically, there will be no attempt to restyle what I write to the level of a guttersnipe.

The Image We Convey

Among those for whom the world holds in the highest regard you will fail to find so much as one so elevated who is unwilling or incapable of producing a cogent, well-phrased, intelligent thought. As B.R. Myers so aptly states, “People who cannot distinguish between good and bad language, or who regard the distinction as unimportant, are unlikely to think carefully about anything else” and I might add that they will find themselves wedged tightly between the ranks of the unimportant and forgotten. Those who fail to educate themselves in the appropriate and proper use of language show but low regard for their own character and reputation. It is as if it was their expressed desire to make themselves look foolish or uneducated or, perhaps worst of all, ignorant.

A poorly written sentence grates like fingernails scratching upon a chalkboard, sending chills down the spine and rattling the nerves. An encounter with a tortured phrase forces the mind to slam on the brakes to avoid collision with the mangled mayhem that strains the eyes. Coarse, crude language reduces to rubbish any statement in which it is injected, provoking illegitimacy to any argument and disparaging the person who would enjoy living in the gutter. And misspelled or misused words only serve to raise confusion and doubt concerning the probity of what has been written and the veracity of the abuser.

Edgar Allan Poe wrote that “A man’s grammar, like Caesar’s wife, must not only be pure, but above suspicion of impurity.” While I will forgive Poe for placing the onus of good grammar solely upon the male half of the species, I wholeheartedly agree with the intent of his sentiment. Ben Marcus wrote that “a misspelled word is probably an alias for some desperate call for aid, which is bound to fail.” I might also add that the misuse of any number of homophones is a sign of a mind in the final stages of terminal mental atrophy, for there is no excuse for the improper use of “its” or “it’s”, “your” or “you’re”, “there” or “they’re” or “their”. And for those who might struggle with the meaning of “homophone” allow me to say that a homophone is a word that is pronounced the same as another word but differs in meaning, and may differ in spelling.

A well-written line, one that gives homage to the language, provides clarity of thought and promotes reasoned understanding of ideas. A poorly constructed sentence, one filled with grammatical errors, misspellings, and poorly chosen words only serve to obfuscate and confuse, to which Michel de Montaigne states, “The greater part of the world’s troubles are due to questions of grammar” and Constance Hale wrote that “The flesh of prose gets its shape and strength from the bones of grammar.”

In The Perpetual Calendar of Inspiration, Vera Nazarian wrote that “Each letter of the alphabet is a steadfast loyal soldier in a great army of words, sentences, paragraphs, and stories. One letter falls, and the entire language falters.” It is no small thing when something as horrific as war or genocide should result from the utterance of a single offensive word or phrase. Words matter, not so much to the one who utters or writes them, but to those who hear or read them. It is thus incumbent upon those who would speak or write to do so with great care, accuracy, and clarity of thought.

Just as Margaret Wolfe Hungerford once wrote that “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder” we should always be mindful that words expressed should always bear beauty and truth to the mind of the receiver. Someone once said, “Say what you mean and mean what you say” and that is true, but what is truer still is to insure that “what you mean to say is what I hear you say.”

As for those who complain that I often use multi-syllable unfamiliar words, I freely admit to such practice for I would rather stain with eloquence than smear with blandness. A new unfamiliar word is like a breath of fresh air that refreshes and reenergizes the written page. I can only offer this advice that quite interestingly comes from two worthy writers: My mother and William Safire. Safire said, “When I need to know the meaning of a word, I look it up in a dictionary” while my mother would simply point to the dictionary and say, “Look it up.”

Let me say a few final words on this subject. William Safire once quipped, “Is sloppiness in speech caused by ignorance or apathy? I don’t know and I don’t care.” To which I am want to add, neither do I.