where the heart rests

What do we hear, what thoughts invade our minds, what imagery appears when we encounter the poetic wisdom of Sirach. Today we heard these words:

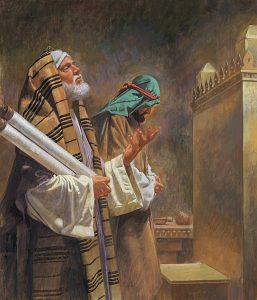

Pharisee and Publican

The one who serves God willingly is heard;

his petition reaches the heavens.

The prayer of the lowly pierces the clouds;

it does not rest till it reaches its goal,

nor will it withdraw till the Most High responds,

judges justly and affirms the right,

and the Lord will not delay.

Two songs sing to us: one of petition and prayer and the other of lowly circumstance and humility. They are songs written indelibly upon the soul and every creature knows the tune.

Yet for many such gentle notes are lost, far beyond their hearing for they listen to the torrid beating of the heart, stifling the whispered voice of God. For the god they worship cares not for the soul but for the random pleasure met by any careless passing thought.

Two men, we are told, find themselves together in prayer, yet only by mere circumstance do they encounter one another; for no purpose other than to plead their case before their God.

One, a Pharisee, prays pompously and impiously, filled with pride and eager to boast of his own righteousness, priding himself on being better than “the rest of humanity—greedy, dishonest, adulterous—or even like” that tax collector nearby. Here we have a man who is, by all accounts, a man of God, one who adheres to the strictest moral code, religiously follows and obeys all of the ancient Law, and yet abides the gravest sin of all, pride.

Elsewhere in Sirach we read:

The beginning of pride is man’s stubbornness

in withdrawing his heart from his Maker;

for pride is the reservoir of sin,

a source which runs over with vice;

because of it God sends unheard-of afflictions

and brings men to utter ruin.

The thrones of the arrogant

God overturns and establishes

the lowly in their stead.

The roots of the proud God plucks up,

to plant the humble in their place:

He breaks down their stem to the level of the ground,

then digs their roots from the earth.

The traces of the proud God sweeps away

and effaces the memory of them from the earth.1

But what is pride and how grave a matter is it?

Saint Thomas Aquinas describes pride in a number of ways. He says first “pride is the appetite for excellence in excess of right reason” while adding what Augustine said in the The City of God, “that pride is the desire for inordinate exaltation: and hence it is that, as he asserts, pride imitates God inordinately: for it hath equality of fellowship under Him, and wishes to usurp His dominion over our fellow creatures.”2

Aquinas asks “Whether the four species of pride are fitting?”3 and then responds by describing them:

- Foolish pride: is thinking you have an excellence which you don’t have, like a child who thinks he is the best basketball player in the world.

- Self-made pride: is thinking you have an excellence from God, and yet believing it is of your own making.

- Self-congratulatory pride: is thinking you have an excellence from above, while boasting that God gave it to you because he knew only you would make the best of it.

- Self-deceptive pride: is thinking you have an excellence from God and he gave it to you because he wanted to do so, BUT … you are really glad others don’t have it and you hope they don’t get it!

How grave a matter is pride?

To this Aquinas writes:

Pride is opposed to humility. Now humility regards the subjection of man to God,… Hence pride properly regards lack of this subjection, in so far as a man raises himself above that which is appointed to him according to the Divine rule or measure, against the saying of the Apostle (2 Corinthians 10:13), ‘But we will not glory beyond our measure but according to the measure of the rule which God hath measured us.’ Wherefore it is written (Sirach 10:14): ‘The beginning of the pride of man is to fall off from God’ because, to wit, the root of pride is found to consist in man not being, in some way, subject to God and His rule. Now it is evident that not to be subject to God is of its very nature a mortal sin, for this consists in turning away from God: and consequently pride is, of its genus, a mortal sin.4

Pride is always contrary to the love of God, inasmuch as the proud man does not subject himself to the Divine rule as he ought. Sometimes it is also contrary to the love of our neighbor; when, namely, a man sets himself inordinately above his neighbor: and this again is a transgression of the Divine rule, which has established order among men, so that one ought to be subject to another.5

How many of us have been guilty of pride at one time or another? Perhaps few harbor foolish pride beyond wishful thinking, but self-made pride is all too common; examples in extremis are but a presidential debate away.

We should always give thanks to God for what he has given us, yet it is but self-serving pride to offer gratitude for the perceived faults and failures of others while lauding praise and exaltation on one’s own deeds and actions, such as the Pharisee “I give you thanks, O God, that I am not like the rest of humanity—greedy, dishonest, adulterous—or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week; I pay tithes on all I possess.”

Have you ever said or heard someone say, “I made it on my own.”, “It’s all because of me.”, “I’ve earned it all myself.”? Only the self-righteous would dare utter such words, implicitly denying that what they have achieved or attained was a gift of God. They do not need God’s love. They need not ask for mercy. They want nothing from God. Perhaps they want nothing of God.

The self-righteous spend their lives in comparison, always anxious to know: who is better, who is worse, who is first, who is last? And just as the Pharisee in the Gospel, those who fail to measure up to their canons of success are deemed unworthy. It is to such people, those “who were convinced of their own righteousness and despised everyone else,” whom Jesus told this parable.

Recognizing that the tax collector was, by all reliable accounts, less than reputable, clearly he was a man with many faults, a sinner, and yet we must admire his humble desire to acknowledge his brokenness and to ask for God’s mercy. He considered himself unworthy, keeping his distance, refusing to raise his eyes to heaven. Does he boast of all his wealth…no. Does he preen with pride at his successes…no. Does he speak ill of his neighbor…no. All he offers is a simple prayer: “O God, be merciful to me a sinner.”

He knows he is a sinner. He knows to whom he is subject. He knows that he does not deserve God’s mercy.

The Pharisee, on the other hand, is condemned by his prayer in spite of being a Pharisee, and in his own eyes a person of importance. Because his ‘righteousness’ is false and his insolence extreme, every syllable he utters provokes God’s anger.

But why does humility raise us to the heights of holiness, and self-conceit plunge us into the abyss of sin? It is because when we have a high regard for ourselves, and that in the presence of God, he quite reasonably abandons us, since we think we have no need of his assistance.

But when we regard ourselves as nothing and therefore look to heaven for mercy, it is not unreasonable that we should obtain God’s compassion, help, and grace.6

Thus it is that Jesus tells us the tax collector went home justified, “for whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and the one who humbles himself will be exalted.” Amen.

Homily for 30th Sunday in Ordinary Time — Cycle C

Sirach 35:12-14, 16-18

2 Timothy 4:6-8, 16-18

Luke 18:9-14

1 Sir 10:12-17.

2 Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicae, II-II q. CLXII a. 1 ad 1.

3 STh., II-II q. CLXII a. 4.

4 STh., II-II q. CLXII a. 5 resp.

5 STh., II-II q. CLXII a. 5 ad 2..

6 Gregory Palamas, Bishop, Homily 2: PG 151, 17-20.28-29.