Won’t you be my neighbor?

Long ago, while not so distant such that it should be forgotten, yet well before the present age of techno-induced catatonic stupor, there were to be found oddments strewn hither and yon which were identified strangely enough as neighborhoods. Not ‘hoods’ mind you, but neigh-bor-hoods, where everyone knew their neighbor and their neighbor’s neighbor, doors were but an impediment for pests and foul weather, and help was never more than a shout away.

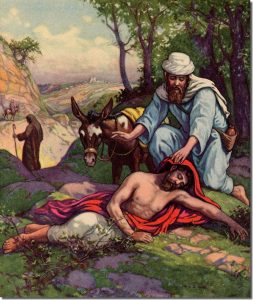

The Good Samaritan

Now this is not a fairy tale or parable to be told for some good purpose; it is nothing but the honest truth, for I know the truth of it because I lived both then and there. I grew up in such a time and place; and, before you ask: no, it was neither Utopia nor Eden nor any other idyllic spot. It was simply home and we knew our neighbors and they knew us.

It amazes to now consider how quickly news did travel then, long before the umbilicus was severed and the tooth was colored blue. Yet faster than a speeding bullet every moment of our lives would fly across the grapevine with far more accuracy in the telling and retelling of it than today.

Did we disagree? Often—yet not as often as when we would agree. Did we like our neighbor? There were days when we did and there were those when we did not. Did we hate our neighbor? There was never any need to go that far. Did we love our neighbor? Without a doubt, for each was dependent upon the other and each relied on the goodwill and love of their neighbors. Did we love and have faith in God? God was at the center of our lives, never religion. Where neighbors chose to worship was of no import for we were neighbors and knew what it meant to be so.

Living in such a neighborhood required an openness to honesty unheard of in this age of transparency. To this point I do recall an event which occurred toward the end of my junior year of High School. Eager to obtain summer jobs, two friends and I excused ourselves from afternoon classes (I forged the notes for the three of us.) I drove the twenty miles to a larger town where we applied for several jobs, which as I recall, we never heard from again.

Later that afternoon as I sped homeward, I was abruptly curtailed by a rather intimidating red light flashing atop a highway patrol vehicle and summarily summoned to appear before a magistrate for far exceeding the posted speed limit.

When I arrived home and as I walked through the door there was absolutely no thought in my head of avoiding an admission of my wayward behavior. There were three compelling reasons for doing so:

- I had been taught from the earliest age to tell the truth, no matter what the cost or penalty might be.

- All traffic citations were posted each week in the local newspaper of which my mother was an employee.

- Yet the overwhelming reason for such ready admission was that the news of my delinquency had preceded my arrival home, no doubt by a passing neighbor as I was engaged in conversation with the patrolman who, as luck would have it, was also a neighbor.

Being a good neighbor doesn’t mean always liking your neighbors but it does mean loving them, caring for them, helping them when they are in need, treating them as you would have them treat you.

Yet…the question remains, most often unspoken, but lingering softly among the tendrils of the mind: just “Who is my neighbor?” And while the answer lies buried deep within our hearts it is the living of it that does betray us, for no matter how often we might hear the parable of the Good Samaritan we still cannot refrain from asking the question.

It is, in a sense, a form of self-denial, for we continue to want to circumscribe precisely whom to call our neighbor. We want to place limits on who should be allowed to reside in our neighborhood.

Surely Jesus doesn’t mean for us to be neighbors to the homeless or the derelicts that live and sleep on the streets does he? Surely he doesn’t mean for us to be neighbors to those holding signs at street corners asking for money or food does he? Surely he doesn’t mean for us to play nice to that unpleasant person down the street who is always complaining about something and anything does he? Surely Jesus isn’t asking me to accept ‘that’ person or ‘that’ family as my neighbor does he?

The truth is—yes; Jesus does indeed expect you to recognize and acknowledge each of those as your neighbor and to love them as you would love yourself and to act upon that love of neighbor by whatever means you might have.

Reflecting upon his own experience with this question, Father John Kavanaugh writes:

“How well I know the excuses, myself a teacher and priest. It was such as I who passed the broken man on the road to Jericho. And I have done the same.

An armless and legless beggar rolling in a Calcutta gutter could not move me to act. I had things to do. He might be part of a racket (what cost he paid for such a ruse!). He will only want more. Others will expect as much from me. My help will only perpetuate his helpless condition. My pittance will do nothing in the long run.

So I, the priest and teacher, passed him by, trying not to notice. It was not the first time. Nor was it the last.

My seeming inability to be a neighbor is hard to reconcile with my professed desire to follow Christ. The will of God still draws close and clear, nudging my heart. And yet I seem at a loss as to the doing of it. The peace I seek is beyond my reach, exceeding both my virtue and my will.

Do these words, then, absolve me of the struggle? No. But they do remind me that I will never want to approach the throne of Jesus. I—the lawyer—pleading my case. Let the unrest continue, so that, as journeys to Jericho recur in my life, I realize that the only times I will find my neighbor are when I am generous enough to become one.” 1

Saint John Paul wrote that:

We should not altogether ignore the question that preceded the discussion of neighbor for there is implied in it no small amount of subtlety that ought to be addressed. A scholar of the law (a lawyer) asked Jesus, “Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” What is nuanced by his question is this: “What is the minimum necessary, the least I have to do to get into heaven?”

Jesus wisely turns the question back onto the lawyer who responds with the correct response: “You shall love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, with all your being, with all your strength, and with all you mind, and your neighbor as yourself.” Consider for a moment that what this truly means is that the least you have to do, the minimum necessary, is everything. You must love God with everything you have and your neighbor as yourself.

Now consider once again the question of neighbor. The lawyer really wanted to know what the minimum number of people he must count as neighbors with whom he must love, didn’t he? And isn’t that what we try to do as well?

And we can see now that Jesus isn’t having any of it, is he? There are no minimums to be considered in order to gain entry into God’s loving embrace; there are only maximums. You are called by Christ to love everyone you meet and in doing so everyone you love becomes your neighbor.

Homily

15th Sunday in Ordinary Time — Cycle C

Deuteronomy 30:10-14

Colossians 1:15-20

Luke 10:25-37

1 John Kavanaugh, S. J., The Word Embodied: Freedom on the Journey, The Sunday Website of Saint Louis University, liturgy.slu.edu.

2 Pope John Paul II, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, 1987: 40.