Loving the mystery

If God were capable of making a mistake – and I do not for a moment consider that to be possible – then I suppose it would be in giving us far too great an appetite for the mysterious. Mysteries come in many forms: whether they appear before us as puzzles, enigmas, conundrums, riddles, secrets, or problems they all present themselves as an itch on the brain that demands us to scratch it, to find an answer to any question, to discover a solution to any problem that is set before us. The mistake that far too often we humans make is to hold fast to the notion that any and all mysteries are in fact solvable, that nothing is beyond our ability to discover, to know, and to understand.

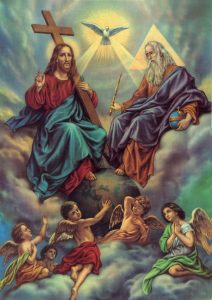

The Trinity

It is the height of our arrogance: our conceit and the hubris of God’s manifest creation that we still believe, just as our first parents believed, that we can be gods, equal to our Creator. How else to explain the dogmatic fervor with which so many so stridently deny even the slightest possibility of the existence of a thing beyond our understanding or something greater than ourselves?

The truth is that some mysteries are simply unsolvable, with explanations that go well beyond what is empirically verifiable. Mysteries such as life and death, God and the Trinity are questions whose answers have been sought for many centuries with nothing approaching a solution ever found. For example, attempts to solve the mystery of God’s existence have often proved to be both vitriolic and intractable, generating endless argument and serious debate with any persuasive or definitive solution yet to be found. Perhaps the best way to describe it would be by paraphrasing Saint Thomas Aquinas “To one who has faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without faith, no explanation is possible.”[2]

There are times when we are faced with such an unsolvable mystery, such as the Holy Trinity, when we accept it in our hearts yet find the itch to understand unbearable. A little story written by Anthony de Mello illustrates this so very well:

“Excuse me,” said one ocean fish to another. “You are older and more experienced than I, and will probably be able to help me. Tell me; where can I find this thing they call Ocean? I’ve been searching for it everywhere to no avail.” “The Ocean,” said the older fish “is what you are swimming in now.” “Oh, this? But this is only water. What I’m searching for is the Ocean,” said the young fish, feeling quite disappointed as he swam away to search elsewhere …

Stop searching, little fish. There’s nothing to look for. Just be still, open your eyes, and look. You cannot miss it. [3]

We find ourselves living in the ocean of the Holy Trinity, completely immersed in the sea of God’s boundless love and presence and all too often all we see is water. We seek but fail to understand and we are disappointed because somehow we feel that we have missed something so very important. Richard Rohr suggests a way of approaching unsolvable mysteries. He says “This life journey has led me to love mystery and not feel the need to change it or make it un-mysterious. This has put me at odds with many other believers I know who seem to need explanations for everything.” His attitude and approach to the mysterious does not in any way suggest that we should not continue to seek in order to find answers to mysteries for which we are capable of solving but rather that we be willing to acknowledge our own limitations and accept on faith those mysteries which are indeed unsolvable.

American History Professor Jill Lepore says that “A mystery, in Christian theology, is what God knows and man cannot, and must instead believe” to which I would further add that to believe is a measure of our faith and our willingness to accept as truth the unsolvable mysteries of God and the Holy Trinity. In the Catechism we find “The mystery of the Most Holy Trinity is the central mystery of the Christian faith and of the Christian life. God alone can make it known to us by revealing himself as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”[4]

One reason, I suppose, that we find it so impossible to explain the Trinity is because to do so would require us to first of all adequately describe God. No matter which language you might use to describe the indescribable and unknowable God, you will forever fail in the attempt. Just as no one can provide the last digit to the definition of PI, God cannot be described or circumscribed by the limitations of any human language. If we cannot solve the mystery of God it follows that we cannot solve the mystery of the Trinity. Perhaps these are mysteries that we should be satisfied to love and feel no need to change or make un-mysterious.

I will leave you with this story written by Masechet Berachot of the Babylonian Talmud. It does not solve any mysteries but it offers us great insight into how God, the Father, Son, and Spirit want each us to live:

It was dusk on the bank of a river that curved from the sea to the mountain. There, perched in the deep bend of a branch of an oak tree, sat a rabbi, and at his feet were students from nations near and far. As the evening slowly reached up from the horizon and spread across the vast expanse of the sky, the rabbi and his students spoke of the great issues of the day. As they did each night, they spoke of issues of the heart, of humanity, and of hope.The rabbi peered into the distance and turned to his students to ask, “Tell me – if you can – how we will know when the night is over and the day has begun?”

The students sat back for a minute and gazed at the horizon and witnessed as the deep blue of evening began to blend with the golden canvas of sunset. And they knew that the rabbi spoke neither of timetables nor of the earth’s rotation on its axis. No, the rabbi spoke of larger things.

After regarding the question for a while, one of the students raised his hand and said, “Rabbi, we will know that the night is over and the day has begun when we can see the difference between a goat and a lamb.”

The rabbi paused and said, “No, that is a good answer, but I don’t think that is it.”

Soon, another student offered her hand and said, “Rabbi, I think the night is over and the day has begun when we can see the difference between a fig tree and an olive tree.”

The rabbi shook his head and said, “No, you have made a thoughtful effort, but that is not it either.”

The students seemed confused and were discouraged. Quietly, they gazed upwards where scattered stars and a full moon replaced the sun and brightened the deep dark of the endless sky.

After a moment, a soft voice could be heard from the bank closest to the river. It came from one of the Rabbi’s most reluctant students. Shy and somewhat hesitant, she began, “Rabbi, I think we will know that the night is over and the day has begun when we can see a rich man and a poor man and hear them say, ‘He is my brother.’”

The student continued, her voice growing stronger.

“When we see a black woman and a white woman and hear them say, ‘She is my sister.’ It will be then when we know that the night is over and the day has begun.”

The rabbi nodded his head, pleased with the wisdom of his student and said, “That is right.”

And to that I will only add, “In the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, Amen.”

[1] Reading I Dt 4:32-34, 39-40; Reading II: Romans 8:14-17; Gospel: Mt 28:16-20.

[2] Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica II-II, Q. 1, Art. 5, “Unbelievers are in ignorance of things that are of faith, for neither do they see or know them in themselves, nor do they know them to be credible. The faithful, on the other hand, know them, not as by demonstration, but by the light of faith which makes them see that they ought to believe them…”

[3] Anthony de Mello, The Song of the Bird.

[4] CCC, #261.